Rethinking Cost in a Changing World

- r91275

- Jun 9, 2025

- 3 min read

For much of the last 30 years, "cheap" was more than a price point — it was a philosophy. A sign of modernity. A promise that globalisation, technology, and scale would steadily reduce the cost of everything: energy, credit, labour, information.

But today, that promise is fracturing.

What used to feel like progress now looks increasingly like exposure — to volatility, bottlenecks, risk, and trade-offs we thought had been engineered away. The era of easy arbitrage is giving way to something else. Something more expensive, more complex, and, perhaps, more real.

What “Cheap” Really Meant

It wasn’t just about affordability. It was about:

Distance without consequence (offshoring without delay)

Leverage without fragility (zero rates without inflation)

Speed without sacrifice (logistics without buffers)

Growth without gravity (capital without cost)

Cheap wasn’t just a function of price. It was a suspension of the normal trade-offs — between security and cost, speed and quality, scale and control. But that suspension was temporary. And reality is catching up.

What systems did we build on the assumption that cheapness was permanent — and what happens as that assumption unwinds?

The Return of Trade-Offs

Costs are rising. Not because efficiency has failed, but because priorities have shifted. Governments are subsidising redundancy. Companies are re-shoring capacity. Consumers are accepting delay over dependence.

This isn’t just inflation — it’s repricing. And it reflects the reintroduction of variables that were previously treated as externalities: resilience, sovereignty, reliability.

“What looks like inefficiency may actually be a form of strategic redundancy — a willingness to pay more for supply chain control, energy independence, or geopolitical optionality.”

In short, cost is being reframed. What used to be considered friction now looks like foresight.

If resilience is no longer free, who can afford it — and who gets left exposed?

The Psychological Shift: From Infinite to Finite

Consumers, too, are adjusting — consciously or not. For decades, they were promised convenience, variety, and ethics — all at once. A world of perfect choices, always available, instantly deliverable. But that illusion depended on hidden costs — environmental, geopolitical, human.

Now those costs are becoming visible. And with them, trade-offs are returning. Time, scarcity, and value are being reweighted. “Good enough” may soon mean “built to last” instead of “delivered tomorrow.”

Can a society trained to expect everything, everywhere, all at once — relearn how to choose?

Implications for Investors

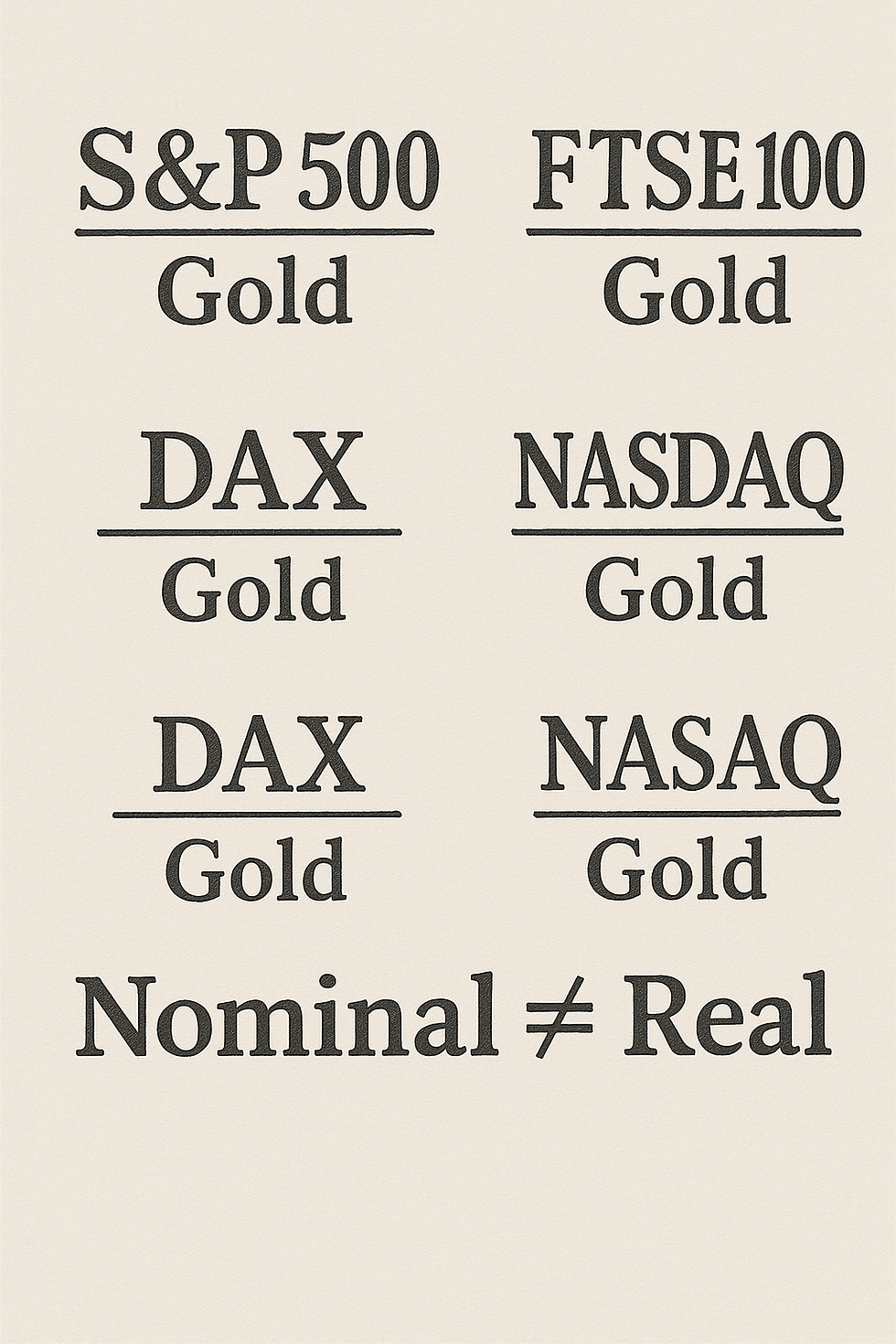

For markets, the end of cheap has several meanings:

Energy: We may be underestimating the cost of securing long-term energy access — especially in a world that wants to decarbonise without de-risking.

Labour: Automation isn’t just about productivity anymore — it’s about navigating wage inflation, demographic shifts, and supply gaps.

Infrastructure: Reinvestment in physical systems — power grids, semiconductors, transport — will define economic resilience more than software ever did.

Geopolitics: Risk premia are back. Regions that were once overlooked for being “inefficient” may now be prized for being stable or aligned.

So where does capital flow? Toward companies that:

Control critical inputs

Operate close to end-markets

Can pass on costs without losing trust

Build necessity, not novelty

Are we investing in the next innovation cycle — or the next layer of insulation?

Rethinking What Value Really Means

The era of “cheap” made us fluent in marginal gains. But as fragility increases, systems that prioritise robustness over return may matter more.

Less leverage, more liquidity.

Less just-in-time, more just-in-case.

Less optimisation, more optionality.

And this shift isn’t just economic — it’s philosophical.

“The end of cheap isn’t just a financial story — it’s a cultural one.In seeing what things really cost, we may finally understand what they’re really worth.”

Comments